Ryan Loflin plans to make history, becoming the nation’s first commercial-scale hemp grower in almost 60 years. In a few days, he will plant his hemp crop on a farm in the far southeastern corner of Colorado. Loflin and a handful of other growers are set to capitalize on hemp’s new legal status in Colorado.

Plenty of financial, operational and legal challenges lie ahead. But cultivating the marijuana look-alike is no novelty pursuit for Loflin, who owns a company called Colorado Hemp. He sees it as a commodity that one day could help reverse the sagging fortunes of rural Colorado.

“I believe this is really going to revitalize and strengthen farm communities,” said Loflin, 40, who grew up on a farm in Springfield but left after high school for a career in construction.

Now he returns, leasing 60 acres of his father’s alfalfa farm to plant the crop and install a press to squeeze the oil from hemp seeds. He’ll have a jump on other farmers, with 400 starter plants already growing at an indoor facility prior to transplanting them in the field.

Hemp is genetically related to marijuana but contains little or no THC, the psychoactive substance in marijuana.

The sale of hemp products in the U.S.— including food, cosmetics, clothing and industrial materials — reached an estimated $500 million last year, according to the Hemp Industries Association.

Yet because of a federal prohibition on growing, all hemp used in U.S. products is imported from foreign countries.

With the November passage of Amendment 64, which legalized hemp in addition to small amounts of marijuana, Colorado becomes a test case on the issue of how much muscle the federal government will flex against states with legal cannabis.

“Once this market is really able to develop — when the feds get out of the way and eliminate the regulatory hurdles — there is definitely potential for measurable economic impact,” said Eric Steenstra, executive director of the Hemp Industries Association.

Springfield banker Jay Suhler allows that there could be economic impact eventually, but don’t count him among the boosters yet. He remains circumspect — even with the drought-induced depression that has afflicted southeast Colorado for much of the past decade.

“We’re a conservative bunch around here,” said Suhler, manager of Frontier Bank.

“I imagine we’d probably stick with our core crops of corn and milo and wheat,” he said. “The first few years you try a new crop, it can be pretty iffy. But in a few years, who knows what might happen?”

Two hundred miles north of Springfield, Yuma County corn farmer Mike Bowman also is preparing to plant hemp this year.

Bowman has been a frequent visitor to Washington, D.C., seeking to persuade federal officials to end the hemp prohibition that makes prospective Colorado growers technically criminals.

A hemp-legalization bill is pending this year in Congress, with bipartisan support.

Until the federal-state legal disconnect is resolved, growers face the challenge of starting an industry without the benefits held by conventional farmers, such as federal crop insurance.

Colorado State University, the state’s premier agricultural research institution, is not studying hemp because of the fear of losing federal contracts.

“The law is clear on this matter, and we do not want to do anything that would unintentionally result in personal criminal liability for CSU employees or that would disqualify the institution from obtaining future government funding,” said Joseph Zimlich, CSU system board of governors chairman, in a recent letter to U.S. Rep. Jared Polis, D-Colo.

However, Zimlich said the board “will look more closely at the issue of industrial hemp research at its May meeting.”

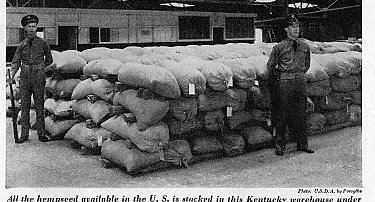

Another practical challenge for farmers is acquiring hemp seed for cultivation. Federal law does not permit the sale or import of nonsterilized seed suitable for growing.

It’s the hemp farmer’s equivalent of what recreational-marijuana activists call “the year of the magical ounce”— a reference to the unanswered question of how people can obtain marijuana for current legal use before state-permitted retail facilities open in 2014.

Bowman said he has friends who have sent him seed from feral hemp plants that are survivors from decades ago, before hemp was ruled illegal in the U.S.

A benefit of the feral plants is that they carry natural genetic resistance to drought — a desirable quality especially for farmers who hope to grow their crops without irrigation.

Like other prospective farmers, Bowman and Loflin plan to experiment with different seed varieties to determine their traits, especially the ability to produce oil.

Seed oil is viewed as the hemp product in highest demand from food and cosmetics manufacturers. Fiber from hemp stalks is a smaller market.

Loflin and business partner Chris Thompson said that with their own oil press, they plan to become buyers or processors of seed from other growers.

Based on data from Canada’s legal hemp industry, hemp seed generates revenue for farmers of $390 an acre, according to Erik Hunter, director of research and development for HempCleans, a Colorado-based advocacy group.

That makes hemp lucrative compared with most other conventional crops.

“I think that once people see the value of hemp,” said Loflin, “it’ll become a no-brainer.”

Steve Raabe: 303-954-1948, sraabe@denverpost.com or twitter.com/steveraabedp